1 Mei 2021

Source: SOHO

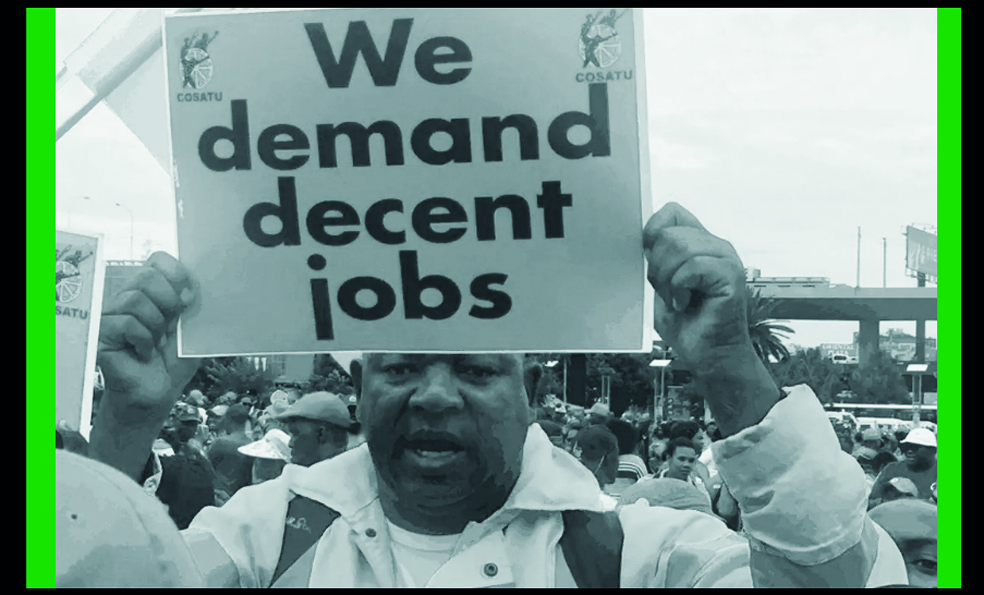

Feature Image: Workers’ Day 2019: A brief history

THE STRUGGLE for a shorter workday, a demand of major political significance for the working class dates back to the 1800s. On 7 October 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, in the United States of America and Canada resolved that eight hours should constitute a legal day’s labour as of 01 May 1886. The Federation also recommended to workers organizations under their jurisdiction that they abide by this resolution by the said date. Since then May Day has been celebrated on 01 May annually.

The first recorded celebration of May Day in South Africa is reported by Ray Alexander to have taken place in 1895 which was organised by the Johannesburg District Trades Council. The next occasion was the visit of British labour and socialist leader Tom Mann, who came to South Africa in 1910. Mann, like Kier Hardie before him, criticized the South African Labour Party (SALP) for its neglect of African workers, and urged the white labour movement to begin to think seriously of organising among African workers. His visit inspired a mood of international worker solidarity and culminated in a mass May Day procession in which all sections of the labour movement participated.

A Call for a More Militant May Day

Source: Left Voice

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 had profound consequences for the development of socialist labour politics in South Africa. Before the war, the Labour Party under Colonel Cresswell was the predominant party political voice of organised white labour in South Africa. By 1914 the Party had succeeded in gaining the support of the majority of the English speaking working class. It was making inroads into the Afrikaans working class as well as the middle class. The 1913 Mineworkers strike, known as the ‘July Strike’ as well as the strike by railwaymen in January 1914 led to the growth of the Labour Party and it managed to win a straight majority in the Transvaal Provincial elections of March 1914. It also captured seats from the government in by-elections, and it was expected to make great strides in the coming general election of 1915.

The outbreak of war in August 1914, however, caused a serious rift within the party, impeding its ‘spectacular growth’. The party became divided into those who called for support of the war and those who were anti-war. At its annual conference in East London in January 1914, an antiwar majority won out. As the governments of Britain and Germany stepped up their war propaganda, increasing pressure to support the British war effort mounted. The leader of the party, Cresswell, was pro-war, and at a special conference in Johannesburg held on 22 August 1914, Creswell’s position in support of the war won a majority. Those who opposed the war motion included W.H. Andrews, S.P. Bunting, Colin Wade and David Ivon Jones. Members of this group formed the War on War League in September 1914, with S. P Bunting as its treasurer.

In 1915 the War-on-War League organised a May Day procession through the streets of Johannesburg. It culminated in a meeting on Market Square, which was addressed by socialists. Eventually those who opposed the war motion resigned or were expelled from the Labour Party. In 1916, May Day was a small affair, celebrated by a social and a visit to the graves of workers killed in the 1914 strike.

At the same time members of the War-on-War League began to think in terms of an alternative to the Labour Party. On the 22 September 1916, The Internationalist Socialist League (ISL) was formed with W. H Andrews as chairman, J.A. Clark as vice-chairman, G. Weinstock as treasurer, and David Ivon Jones as secretary. In 1917, May Day acquired a new international significance as a result of the Russian Revolution. In South Africa the ISL organised a May Day rally, where for the first time an African, Horatio Mbelle, an articled clerk, was billed as one of the speakers. The rally, however never took place as mobs of soldiers and civilians filled the streets, preventing the rally from taking place. The next year (1918) the ISL held its May Day demonstration in the coloured area of Ferreirastown, Johannesburg, Transvaal (now Gauteng) and made history by having two Black speakers address the meeting. They were William Thebedi and Talbot Williams of the African People’s Organisation (APO).

After the war there was resurgence in the militancy of the white labour movement, and May Day became an annual event, but it was a white labour affair. It would not be until 1928 that May Day would be taken up by African workers en masse. In that year thousands of African workers took part in a mass May Day march that dwarfed the small Labour Party’s demonstration which consisted of white workers only. Between 1928 and 1948 May Day became an annual event, drawing workers of all races.

On the 64th Anniversary of May Day, in 1950, the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) called for a May Day strike to protest against the Suppression of Communism Act. The strike resulted in police violence that led to the death of 18 people across Soweto. Nelson Mandela, later South Africa’s first democratically elected President, sought refuge in a nurses’ dormitory, overnight, where he sheltered from the gunfire.

Less than two months later, the CPSA was forced by the regime to dissolve, and the African National Congress (ANC) took over the planning for a ‘Day of Mourning’ for those who died in the May Day strike. They also called for the day to be celebrated as Freedom Day in the future. At this period (1950), the National Party government was a “new kid on the block”, as it just won the 1948 general election and was tightening its grip on the Black majority of the country.

In June 1952 almost two months after May Day the largest scale non-violent resistance ever seen in South Africa, the Defiance Campaign, which was the first campaign pursued jointly by all racial groups under the leadership of the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Indian Congress (SAIC) took place.

This was followed by the Congress of the People (CoP), in 1955, where the Freedom Charter was born. The campaign for the Congress of the People and the Freedom Charter united most of the liberation forces in South Africa. Nothing in the history of the liberation movement in South Africa quite caught the popular imagination as the Congress of the People campaign. It served to consolidate an alliance of the anti-apartheid forces of the 1950s composed of the ANC, the SAIC, the South African Coloured People’s Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) into a non-racial united front known as the Congress Alliance.

The government intensified its banning orders on political activists belonging to the Alliance. Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, James Moroka and others were tried under the Suppression of Communism Act for their leadership role in the Defiance Campaign. All 20 accused were sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment with hard labour, suspended for two years.

The 100th anniversary of May Day was commemorated on 1 May 1986. The South African labour federation Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), formed in December 1985, demanded that May Day be recognised as a public holiday, Workers Day, and called for a stay-away.

It was supported by various organisations, significantly the National Education Crisis Committee (NECC) and the United Democratic Front (UDF), as well as many traditionally conservative organisations – such as the African Teachers Association, the National African Chamber of Commerce, and the Steel and Engineering Industries Federation of South Africa (SEIFSA), the metal industry employers’ organisation.

Subsequently, more than 1,5-million workers observed COSATU’s call, joined by thousands of school pupils, students, taxi drivers, hawkers, shopkeepers, domestic workers, self-employed and unemployed people. While the call was less successful in some regions, in the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vereeniging (PWV) area, (now Gauteng Province), the heartland of industry, the response was massive. Rallies were held in all the major cities, even though many of these were banned in advance by the state.

The majority of South Africa’s workers had unilaterally declared the day a public holiday and stayed away from work. Premier Foods became the first large employer to declare 1 May and 16 June as paid holidays. Following this, many other companies followed suit.

The media acknowledged that the majority of South Africa’s workers had unilaterally declared the day a public holiday, and Premier Foods became the first large employer to declare 1 May and 16 June as paid holidays. Following this, many other companies bowed to the inevitable. (*)